About 13 minutes into The Life of Chuck, a sudden realization hits like a ton of bricks: this is a stark portrayal of death through the lens of a secular mind that has rejected Jesus Christ.

Some may argue this is a bold leap for a film based on a Stephen King novella, but the story’s core elements—unfolding from death to life in a reverse narrative—make a compelling case for this interpretation. The film opens (in forward chronology, its finale) with a global apocalypse: skyscrapers crumble in New York City, mass blackouts paralyze society, and headlines bizarrely tally down to “Charles Krantz: 39 Great Years!”

This cataclysmic collapse frames Chuck’s death from a brain tumor as the unwitting catalyst for universal entropy—a quiet, anonymous passing that triggers cosmic disorder. Society, glimpsed through cameos like Chiwetel Ejiofor’s teacher and Karen Gillan’s cop, clings to denial amid riots and evacuations, yet no redemption halts the inevitable doom. Fragmented memories of Chuck’s life flicker like dying embers, offering no solace.

This plot device allegorizes the biblical consequence of collective unregeneracy: a world hurtling toward fiery judgment without Christ’s mercy. Revelation 20:11-15 (KJV) describes the Great White Throne Judgment, where the unrepentant are cast into the lake of fire: “And I saw a great white throne… And whosoever was not found written in the book of life was cast into the lake of fire.” Chuck’s uncelebrated death—mythologized only in its apocalyptic aftermath—mirrors the “unprofitable servant” of Matthew 25:30 (KJV), whose lack of fruitful faith yields outer darkness.

The film’s ironic billboards (“Thanks, Chuck”) mock any lasting earthly impact, echoing Ecclesiastes 9:5 (KJV): “For the living know that they shall die: but the dead know not any thing, neither have they any more a reward; for the memory of them is forgotten.” Without spiritual rebirth, Chuck’s “great years” dissolve into apocalyptic vanity, a warning that human accolades cannot avert divine wrath (Hebrews 9:27, KJV: “And as it is appointed unto men once to die, but after this the judgment”).

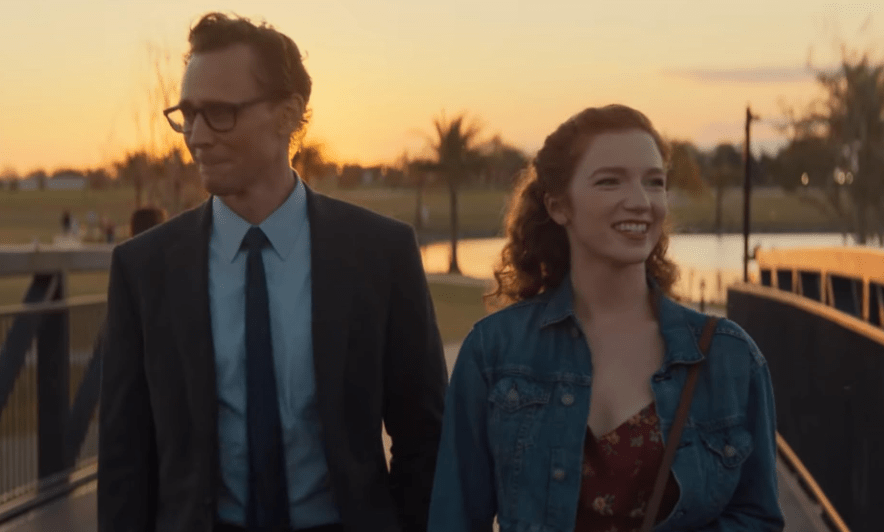

The second act shifts to Chuck’s young adulthood, portraying him as a laid-off accountant (Tom Hiddleston) dancing exuberantly in the rain at a neighborhood block party, romanced by a woman (Annalise Basso) amid brass-band revelry. Yet his job loss leaves him stranded at a bus stop in quiet despair, symbolizing stalled progress and isolation.

Flashbacks reveal his budding romance curdling into unspoken grief, with Chuck retreating into solitude as life moves forward for others. This chapter captures the unsaved life as a cycle of fleeting pleasures overshadowed by inevitable sorrow, devoid of an eternal anchor.

Proverbs 14:13 (KJV) encapsulates this: “Even in laughter the heart is sorrowful; and the end of that mirth is heaviness.” Chuck’s rain-soaked dance—a burst of unbridled joy—evokes the world’s vain pursuits, but his abandonment at the bus stop underscores their futility without Christ.

Psalm 78:32-34 (KJV) further illuminates this: “For all this they sinned still, and believed not for his wondrous works. Therefore their days did he consume in vanity, and their years in trouble.” Chuck’s relational highs devolve into isolation, his potential for connection untethered by faith.

The act’s poignant close, with Chuck alone under streetlights, prefigures the unregenerate soul’s fate: 2 Thessalonians 1:9 (KJV) warns of those who “shall be punished with everlasting destruction from the presence of the Lord.” Chuck’s “multitudes,” as the film calls his inner complexities, remain fragmented without Christ’s unifying rebirth.

The reverse arc of The Life of Chuck—from joyful inception through hollow midlife to apocalyptic erasure—serves as a secular parable for the biblical trajectory of the unreborn: creation’s spark dimmed by sin’s entropy, culminating in judgment.

Chuck’s quiet heroism—small kindnesses rippling faintly against doom—highlights the insufficiency of human goodness alone. The film’s optimistic tone, celebrating life’s beauty amid decay, paradoxically strengthens this reading: such affirmations ring hollow without eternal hope, pointing viewers to John 3:16 (KJV): “For God so loved the world, that he gave his only begotten Son, that whosoever believeth in him should not perish, but have everlasting life.”

The Life of Chuck highlights motifs of vanity, loss, and fleeting legacy framing Chuck’s tale as a cautionary celebration of what might be redeemed through Christ, lest it unravel into dust.

Director Mike Flanagan is known for blending horror with humanism but this film balances haunting visuals with emotional depth, though its secular lens limits its resolution. The performances, particularly Hiddleston’s nuanced portrayal of Chuck, elevate the character study, but the lack of a redemptive ending leaves a bittersweet aftertaste.

The Life of Chuck is a beautifully crafted meditation on life and death, showcasing the sad reality of a secular worldview. Its refusal to offer a happy ending, while honest, underscores the void left by rejecting eternal hope, making it both compelling and unsatisfying.

3/5

Leave a comment